This summer, I had the privilege of attending an amazing talk by Larry Guth on the “no rectangles problem.” The problem is very simple:

In an grid, how many dots can you place such that no four dots form a rectangle?

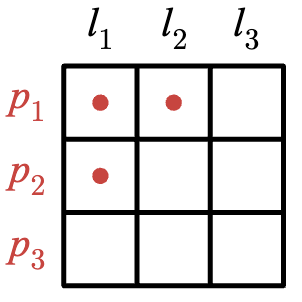

So, for example, we could arrange dots as follows in this grid:

In this particular arrangement, there are 8 dots, and we can’t add any more without creating a rectangle. Actually, there technically does exist a rectangle in our grid, as you might have spotted…

But, for our purposes we don’t count skewed rectangles like this one. However, one certainly could consider that as a variation of the problem. And, in fact, there are many related questions to ask. For now, let’s consider the obvious ones: What is the maximum number of dots we can place? Is there an optimal strategy? What do optimal solutions look like?

Larry Guth mentions in the talk that on average, optimal solutions tend to have the same number of dots in each row and column. This makes some intuitive sense because if we place dots in every square in one row, like so…

…we can place only one dot in each remaining row, as any two dots in the same row would form a rectangle. We’d get stuck at an arrangement like this, which doesn’t seem so great.

Apparently, a decent strategy is actually randomly placing dots until we can’t place anymore without forming a rectangle. (This sort of checks out with the idea that we want approximately the same number of dots in each row and column.) From running some computations, they found that this strategy yields dots per row/column, so the total number of dots we can place is

. It seems that they somehow found that optimal arrangements would have on the order of

dots, so each row/column would have about

dots. (The first example we gave has

dots per row and column, so it’s probably pretty optimal.)

Also apparently, in general, nobody has found a better strategy than just random placing! But, there is a construction which gives an optimal arrangement for some grid sizes . Here’s where the magic comes.

The construction is based off the idea that we can get from a system of points and

lines on the plane to an

grid with no rectangles. Take, for example, these three points and lines on the plane.

We correspond the rows to the points, and the columns to the lines, and we place a dot in the grid if the point lies on the line. So, the above drawing results in the following “no rectangles” grid.

It’s pretty easy to see that if we go in this way from a diagram of distinct points and lines to a grid of dots, there will never be a rectangle, and this is because two points uniquely define a line.

However, the converse isn’t true—we can’t always go from a “no rectangles” grid to a drawing of points and lines on the plane—and this isn’t immediately obvious. The idea for why this is not always possible lies in the fact that the Fano plane cannot exist in the Euclidean plane with straight lines. As a hint, try to come up with a drawing of points and lines which would give rise to this “no rectangles” grid:

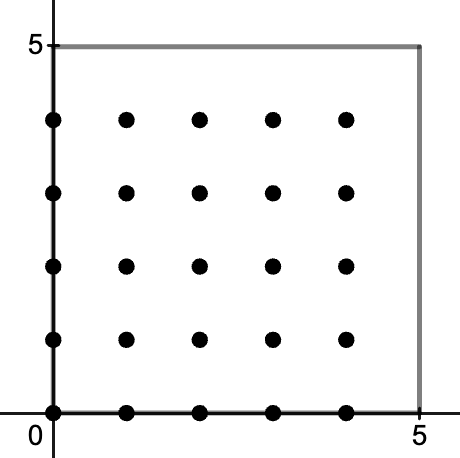

This is cool and all, but we are digressing. How do we go from points and lines to an optimal solution? We consider, of course, points and lines in a finite field! That is, consider lattice points mod a prime number . For example, this would be the lattice points mod 5. Our plane is now finite, and any time we cross the gray boundary, we teleport back to the same spot on the other side of the square.

There are many distinct points on our plane, and there are also

many distinct non-vertical lines on our plane (since each line can be defined as usual by the equation

). The lines look sort of strange because they are allowed to “teleport” across the boundary. For example, below is a drawing of the “line”

in our affine plane:

It’s not too hard to see that each line crosses exactly points, and each point will be covered by exactly

lines. As a result, we can immediately construct a “no rectangles”

grid with

dots on each row and column, and since

is the square root of the dimension of our grid, this is an optimal solution!

Although we can only do this for grids, given an

grid, it doesn’t seem like a bad strategy to make this construction for some

and restrict the “no rectangles” grid to some

subgrid of the

grid. Since given an integer

, there will on average be a prime

away, we can approximate

. If we assume the distribution of dots is generally even in the

construction, we would expect

dots per row/column, which tends to

asymptotically!

Hmm, if I’m not missing something, it seems like this could be a better strategy than random! Even if a random subgrid is not very good, we could probably prove that at least one of the subgrids would have a pretty large number of dots.

Anyways, that’s all from me for probably another 4 months :). This problem was really interesting, and of course, I can’t resist a clever finite field solution when I see one. And there are still so many directions we could keep thinking about the problem (for example, we could consider certain subsets of lines in the affine plane to include, which could maybe generalize our solution to rectangular grids too).

Source: “The No Rectangles Problem” lecture by Larry Guth (given at the SPUR/RSI lecture series on 7/17/24).

Leave a comment